Introduction

Britain has entered the 2020s feeling divided and exhausted. Half of us cannot recall any time when the country seemed so divided. By a margin of almost five to one, Britons worry that our political divisions will lead to increasing hatred. The story of a country trapped in a cycle of disagreement and division now risks taking hold, as debates about Covid-19 remind us of the deep divisions of the Brexit years.

This is what inspired More in Common to launch the Britain’s Choice project: to better understand how we build a more united and cohesive Britain, one that is more resilient to the forces of division. The project has begun with a landmark report, Britain’s Choice: Common Ground and Division in 2020s Britain. It is the product of thousands of conversations and surveys conducted across the UK over an 18 month period. It is one of the largest-ever national studies of our country’s social psychology. It uncovers insights about British people from every walk of life.

We have been learning about what people value most in life, how they feel about their community, and what they think about a whole range of issues. Alongside a lot of data, we are sharing more than a hundred quotes straight from the mouths of participants in the study. And we have included some real-life profiles of people who took part. The picture of our country that comes from this study is sometimes surprising – and compared to the picture we get from our screens every day, it gives us much reason for hope.

Key takeaways

People in Britain are not as deeply divided as is often assumed. There are fault lines in our society, and many of them are examined in this study. What we find consistently is that when people focus on those fault lines, it often obscures the common ground. Whether it is what makes us proud about the UK, our ideals for the future, or even the way we think about many of our country’s most pressing concerns, people in Britain have more in common than divides us.

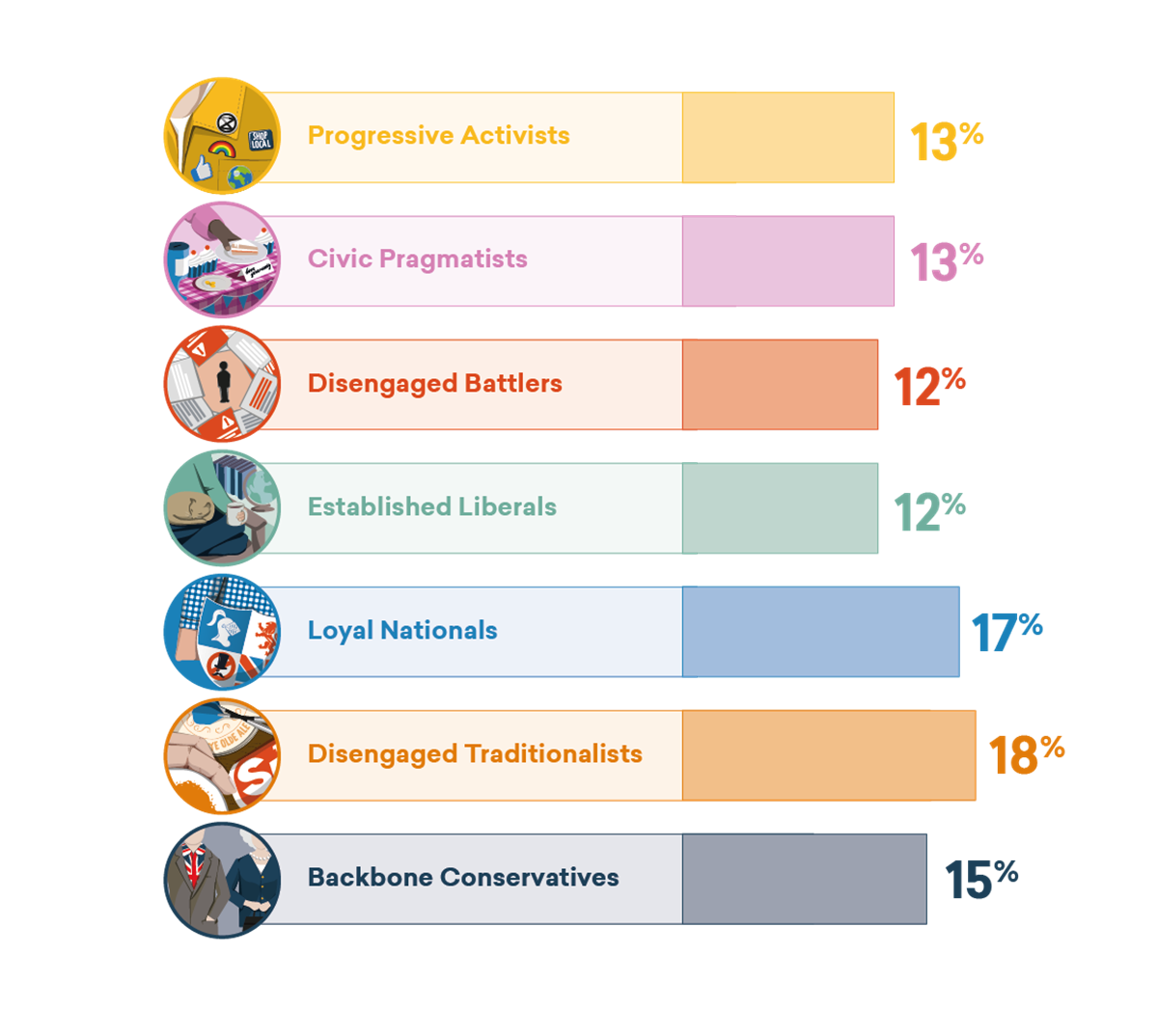

At the heart of this study is a new map for understanding British people, based on their psychology and core beliefs. The model has been developed through More in Common’s work in the United States, France, and Germany, but the seven groups are uniquely British. We think some of them, if not all, will feel at least a bit familiar.

Understanding those seven groups, each with their distinctive values and priorities, helps us better understand our differences and our common ground. Overcoming divisions, whether shallow or deep, requires more than just good feelings towards each other. We each need to make the effort to understand people who are different from us. That’s a key aim of this mapping of Britain’s seven segments. If we better understand our differences, we can be far more effective at preventing healthy democratic differences from becoming dangerous divisions.

It is Britain’s choice whether we come together or allow the forces of division to tear us apart. Everywhere across the world, societies are being divided in “us-versus-them”. Resisting the pull of those forces is not easy, but we can make the choice not to let those forces overwhelm us. The goal of this report is to create an evidence base for that work, so that people who want to make a difference can be more effective in their efforts, and more confident of their results.

The 7 groups

We set out to better understand what divides as well as what unites us. Our conclusion is that Britain is not divided into two opposing camps of Remain versus Leave, left versus right, North versus South, or rich versus poor. Instead, we find seven distinct groups, who are distinguished not by who they are, where they are from, or what they look like, but what they believe.

There are more detailed profiles for each of the groups, but here’s a quick snapshot of each group:

Progressive Activists (13 per cent of the population): A vocal group for whom politics is at the core of their identity, and who seek to correct the historic marginalisation of groups based on their race, gender, sexuality, wealth and other forms of privilege. They are politically-engaged, critical, opinionated, frustrated, cosmopolitan and environmentally conscious.

Civic Pragmatists (13 per cent of the population): A group that cares about others, at home and abroad, who are turned off by the divisiveness of politics. They are charitable, concerned, exhausted, community-minded, open to compromise, and socially liberal.

Disengaged Battlers (12 per cent of the population): A group that feels that they are just keeping their heads above water, and who blame the system for its unfairness. They are tolerant, insecure, disillusioned, disconnected, overlooked, and socially liberal.

Established Liberals (12 per cent of the population): A group that has done well and means well towards others, but also sees a lot of good in the status quo. They are comfortable, privileged, cosmopolitan, trusting, confident, and pro-market.

Loyal Nationals (17 per cent of the population): A group that is anxious about the threats facing Britain and those facing themselves. They are proud, patriotic, tribal, protective, threatened, aggrieved, and frustrated about the gap between the haves and the have-nots.

Disengaged Traditionalists (18 per cent of the population): A group that values a well-ordered society, prides itself in hard work, and wants strong leadership that keeps people in line. They are self-reliant, ordered, patriotic, tough-minded, suspicious, and disconnected.

: A group who are proud of their country, optimistic about Britain’s future outside of Europe, and who keenly follow the news, mostly via traditional media sources. They are nostalgic, patriotic, sturdy, proud, secure, confident, and relatively engaged with politics.

Our research

More in Common has worked with data scientists at YouGov and social psychology academics to build a model that maps the British population not according to their party, age, income, or other demographic factors, but according to their values and core beliefs. We engaged a representative group of more than 10,000 people, with a specially designed series of questions that helped us understand people’s psychology ―questions about their identity and the basic values and beliefs that influence the way they see the world.

By focusing on core beliefs, we discovered the hidden architecture that animates the lives and views of British people. We used an advanced statistical process called k-means clustering to identify groups of people with similar core beliefs. The result of this mapping is a unique portrait of the British public that we believe is both more revealing, more long-lasting, and more actionable than typical surveys.

Once we understand the values that distinguish people in each group, we see that time after time, those seven groups are consistent with those values in their views and behaviours – on immigration, white privilege, inequality, community life, national pride, protecting the environment, following public health guidelines and on many other issues. Knowing that someone is a Disengaged Battler, for example, tells us much more about them than being told their age, or income, or what party they voted for in 2019.

Of course, public opinion research only tells a partial story. But the Britain’s Choice research is detailed, the sample is large, and our approach was open-ended. We were determined to let the data tell us about people in Britain organically, rather than proving pre-baked assumptions. The conclusion? A very different story than the tale of a Britain split into two camps and certain to divide further.

Britain’s kaleidoscope

Two hundred years ago, a Scottish scientist named Sir David Brewster created the world’s first kaleidoscope, an invention that has remained popular with children ever since. As a child holds a kaleidoscope to the light and turns the cylinder, they see the coloured fragments of glass reassemble and cluster together in different formations. With each turn, the light diffuses those colours in different and often brilliant ways.

The kaleidoscope is a powerful image for today’s Britain: not a country divided into two camps, but a country that has different formations across different issues. Differences are normal for a healthy democracy. Indeed, our parliamentary tradition of disagreement and debate is a proud part of British history that has been exported throughout the world. Where differences become more dangerous is when they become divisions, and we become locked into an ‘us-versus-them’ conflict and members of a group converge across a range of issues.

Britain’s strength is that our seven groups cluster in different formations from one issue to the next:

- On issues that involve our traditional institutions and social trust, Established Liberals, Civic Pragmatists and Backbone Conservatives cluster together on the one hand, while on the other hand Disengaged Battlers, Disengaged Traditionalists and Progressive Activists share a distrust of institutions.

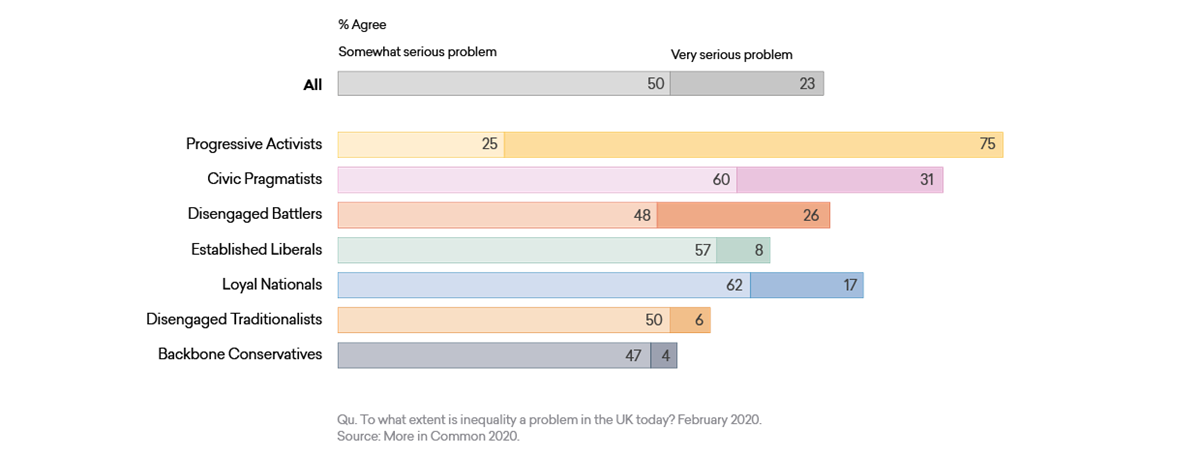

- On issues of inequality and economic policy, there is a cluster of Progressive Activists, Loyal Nationals, Civic Pragmatists, Disengaged Battlers, and to a lesser extent, Disengaged Traditionalists – with Backbone Conservatives and Established Liberals on the sidelines.

- On issues of immigration and race, Loyal Nationals, Disengaged Traditionalists, and Backbone Conservatives cluster together, while Progressive Activists, Civic Pragmatists, Disengaged Battlers, and Established Liberals cluster with similar views.

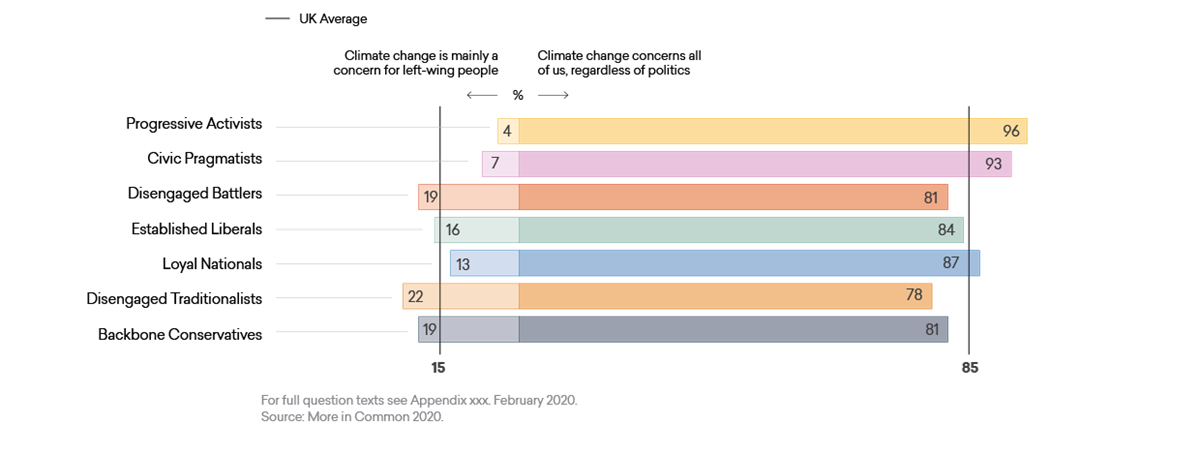

- There is consensus across all groups on our need to protect the environment and take action on climate change, with especially strong support from Progressive Activists, Civic Pragmatists, and Loyal Nationals.

The result is that we are not locked into two fixed, opposing camps – and different issues unite us with different groups.

Exhausted Britain

We have entered the 2020s with Britons seeing the country as deeply divided after the Brexit years. Some 50 per cent of Britons told us that they had never seen the country so divided. Just 1 in 10 felt that we have been through more divided times before.

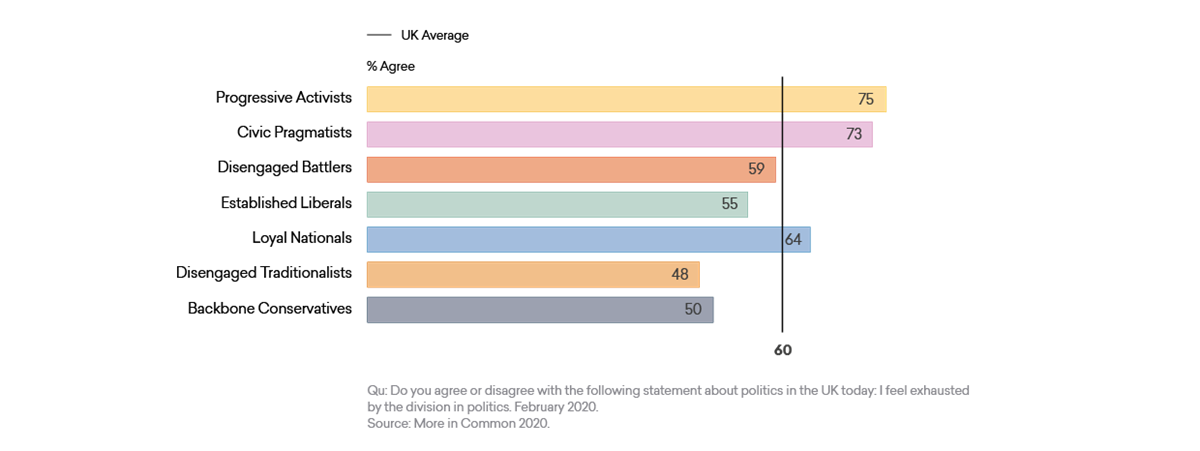

In our public debates, it seems that we no longer just disagree. We reject each other’s premises and doubt each other’s motives. We question each other’s character. We block our ears to diverse perspectives. Social media has become a hotbed of outrage, takedowns, and cruelty—often targeting total strangers. No wonder that 60 per cent of us feel exhausted by the division in our politics – something we blame first on political parties, and second on social media.

The good news is that most of us want to move forward from this division. In our conversations we have heard so many people say they feel relieved that the bitter years of debate about Brexit are almost behind us. 7 in 10 say that for the future of our country, it is important that we stick together despite our different views. But to do that, we need to understand the differences that lie behind our divisions, and the fault lines that could open up in the future.

Our fault lines

The good news from the Britain’s Choice study is that many of the fault lines in our society are not as deep as we might imagine. Looking at our differences through the lens of our segments often helps us better understand these fault lines, and go deeper on how we can prevent differences widening into divisions.

Left and right: Relying on a left/right spectrum to understand how people in Britain think today is like seeing a tapestry as only a black and white image. It misses much that is distinctive about people’s beliefs and values. We examine this fault line in some detail, but three key facts jumped out from our study:

- Just 23 per cent of Britons have a strong left- or right-wing political identity.

- Only 30 per cent feel that left and right labels are still relevant.

- More than half the population identify themselves with the centre (as centre, centre-left or centre-right)

Brexit divisions: The debate over the UK leaving the European Union is unusual in the extent to which it engaged British people’s identities, changed voting patterns, and disrupted politics. The Leave campaign was particularly effective in engaging people who have otherwise been detached from politics, tapping into their sense of frustration with the system and their feelings of not being represented by the establishment. More than other issues, the divisive Brexit years has left scar tissue of hostility between strong Remain and Leave supporters. But so long as those divisions are not replicated on new and different issues, over time those scars can heal.

Age: Age is often discussed as one of the greatest dividing lines in the United Kingdom, especially in voting and on attitudes to issues such as Brexit, race and immigration. But there is an important distinction between differences in attitudes and divisions between people. Differences do not necessarily create generational conflict, because these differences are mediated by family and friendship bonds. Generalisations about ‘the young’ and ‘the old’ also fail to capture the wide range of views within each group. Instead, views are more often influenced by underlying values and core beliefs, rather than age. We do not find any evidence that ‘us-versus-them’ dynamics between old and young people are taking hold in the UK.

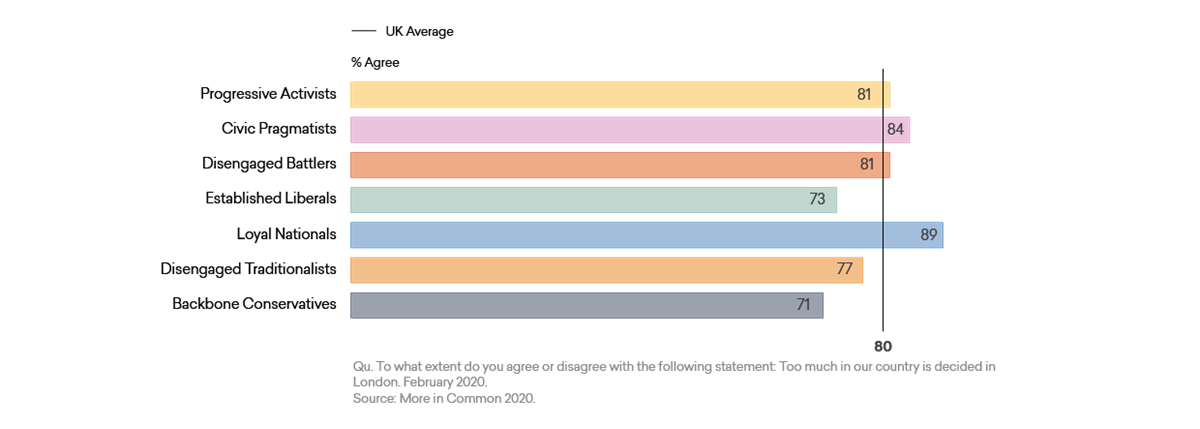

Nation and region: We often differ on the distribution of power and resources within the UK – but there is widespread agreement that too much is hoarded in London, just as too much money is held by too few hands in our society. National and regional divisions in the UK are a complicated mosaic, but there is consensus that more should be decided at a local level. Even those in London are more likely to agree than disagree that too much in our country is decided in London. But the story of our regional differences needs more nuance than simple divisions such as North and South – often there are more differences not between regions but within them, such as between core cities and struggling post-industrial towns.

British identity: We are an unusual country, in the way in which our sense of identity involves different layers. Most of us are proud to be British, but also to belong to a nation within the UK. Many of us come from different backgrounds or feel attached to local identities, but most of us don't feel the need to reduce identity to either/or choices. We can be proud of being British, being an immigrant and being Scottish at the same time. British identity is in some ways a bit of a muddle, but that makes us more resilient to efforts to divide us into ‘us-versus-them'.

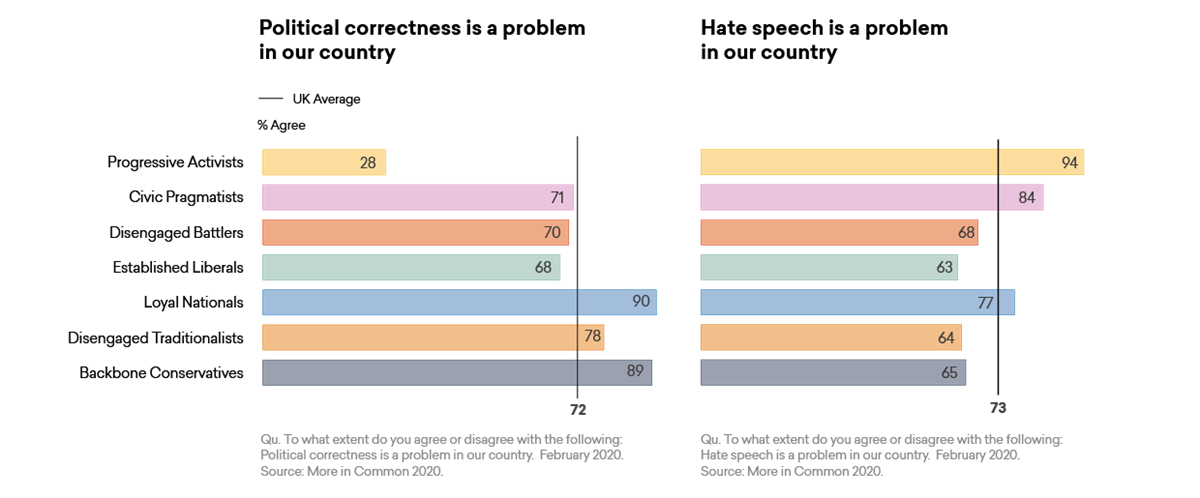

Culture wars: On many of the issues that are most hotly contested, many of us can see two sides of an argument. Culture wars seek to exploit the weaknesses in our fault lines. But most of us do not want to fight the culture wars. More than 7 in 10 Britons think that both hate speech is a problem, and political correctness is a problem. Most recognise the reality of white privilege, and 3 in 4 of us think racism is a serious problem, but many also worry that some people are too sensitive about issues concerning race today. We have pride in British history, while understanding also that it is complicated. Most of us think that we should focus on the future, not the past.

The power of community

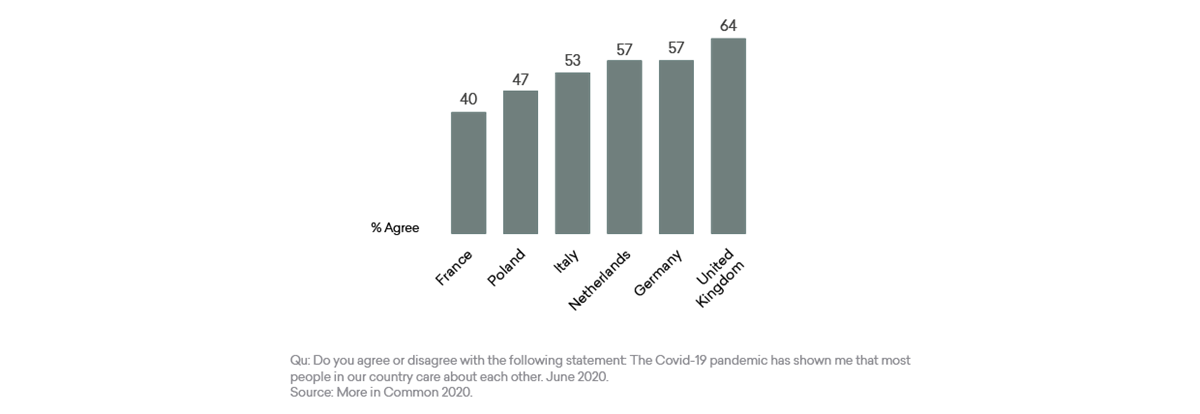

Local community is a distinctive strength of life in many parts of Britain. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, 3 in 4 Britons felt that most people in Britain were kind. The pandemic allowed us to see kindness in action, as people came to each other’s aid within local communities and across the country.

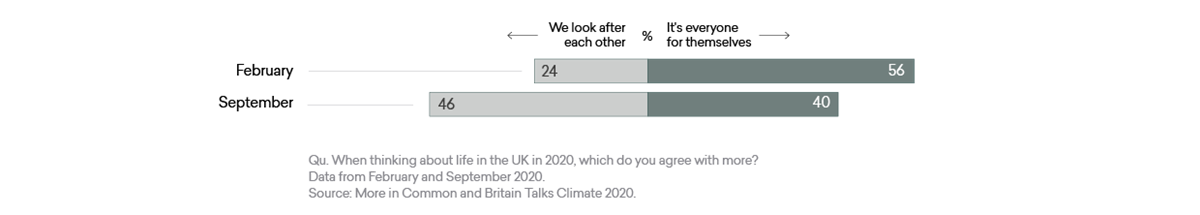

A majority of people believe that our communities have become more caring, connected and kinder during the Covid-19 pandemic. We look out for each other more, and we feel it's not just everyone for themselves. More than other western democracies, we feel that our concern for each other’s well-being has improved since the outbreak of the pandemic. We have also become more aware of inequality and of the way that Covid-19 affects minorities within our communities.

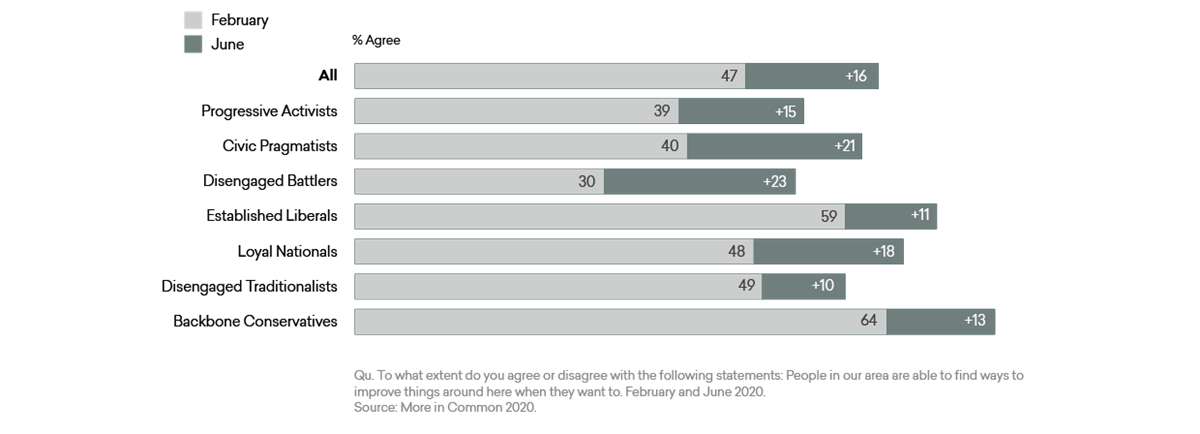

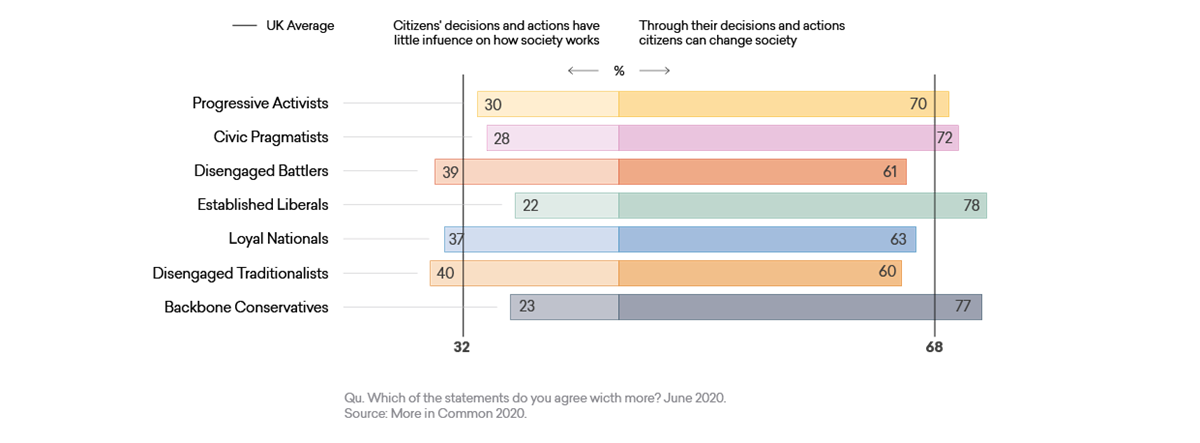

More of us now think we are part of caring communities. Most of us think it’s important to be part of a strong community, but some of us have never felt part of one. Now, more of us have. Many more people are also feeling that they can make a difference in their communities - a sign of emerging community power. Two in three of us think that through our decisions and actions, we can make a real difference in our community (a 16% increase from pre-pandemic levels).

Some of the biggest and most positive differences have been experienced by those of us who feel least connected to others. Across the whole country, in communities of all shapes and sizes, people are understanding the meaning of community again.

Our common ground

A big discovery of the Britain’s Choice study is just how much common ground there really is among Britons – in our shared sense of pride, the things we love above our country, what we think is wrong with it, and the need to fix it. We also have a surprising amount of common ground on how to go about change – starting with bringing back the British values of common sense and compromise into politics and society.

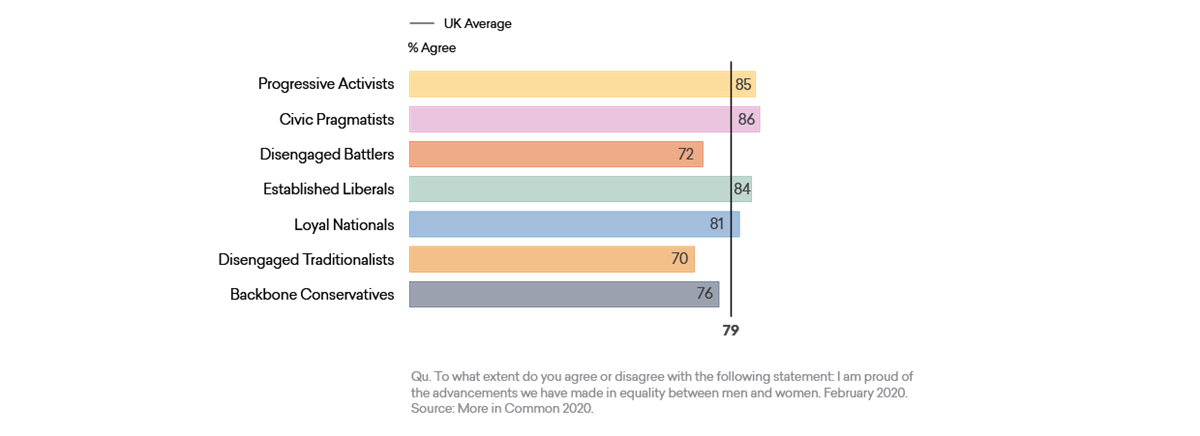

We share a sense of national pride in many things - our seven groups might disagree on a lot, but they are united in saying that nothing makes them more proud of Britain than the NHS. Across society we also value our countryside and our volunteer traditions, and much more. Again, we find a society-wide sense of pride in Britain becoming a more tolerant, equal and diverse nation. Our advances in gender equality also makes us proud.

Our pride in the countryside means that protecting our environment and acting on climate change concerns all of us, regardless of politics – even if sometimes we might use different words to describe why. The improvement in the environment during Spring 2020 have also convinced us that changing human activity really can result in improved environmental impact.

We share a deep concern to close the gap between the haves and the have-nots – reflected during 2020 in the way that many people responded to footballer Marcus Rashford’s campaign to help children in poverty across Britain. We know that hard work in our society is not adequately rewarded, and two-thirds of us feel that the whole system is rigged in favour of the rich and influential. We want to see things change.

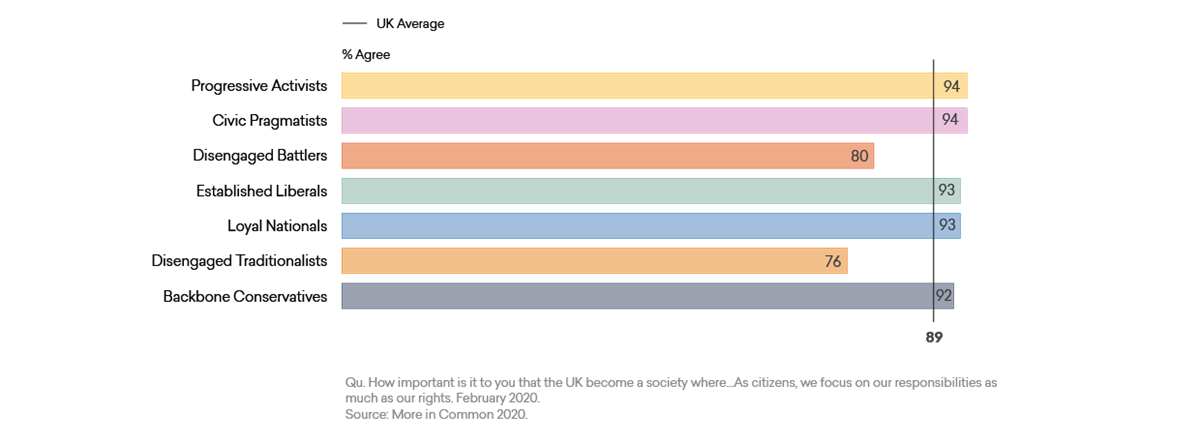

We want to see change, but we don’t want a revolution. We share common ground in believing that responsibilities are just as important as rights, and the number one value in our ideal Britain is that we are a hardworking people – as well as more environmentally friendly and more compassionate people.

We want to see our local communities made stronger, and power to be distributed more fairly across the country.

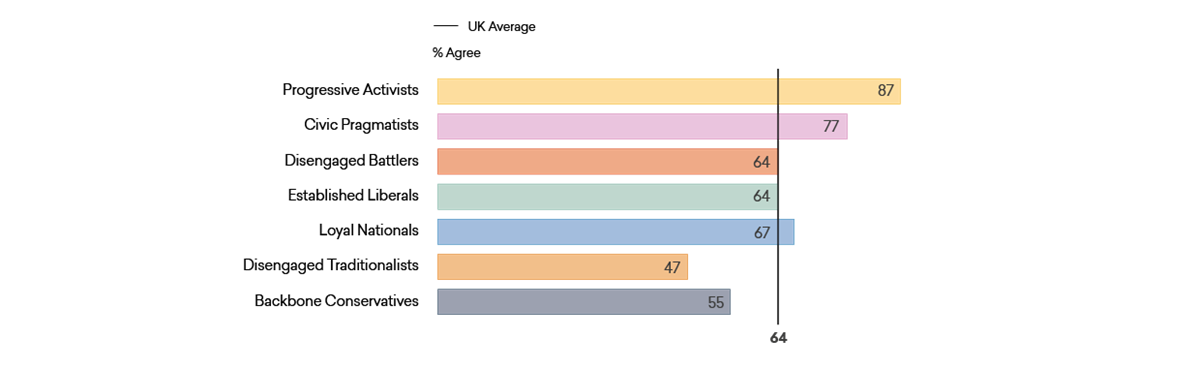

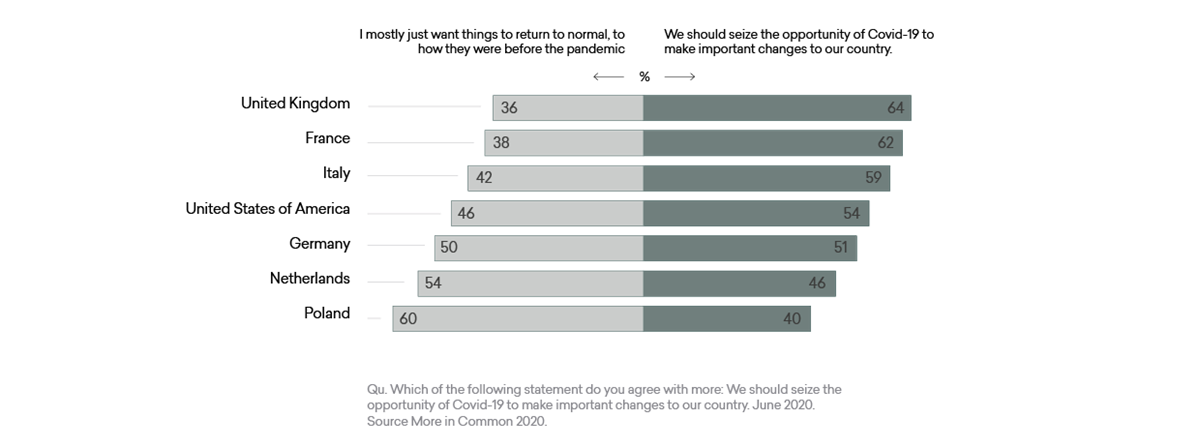

We find common ground in our aspiration to seize the opportunity of Covid-19 to make important changes in our country, and we want leaders in our country to compromise to make this common ground dream, a reality. All this is common ground among large majorities of people across the United Kingdom.

Britain’s Choice

Britain faces a choice about the path we take into the 2020s.

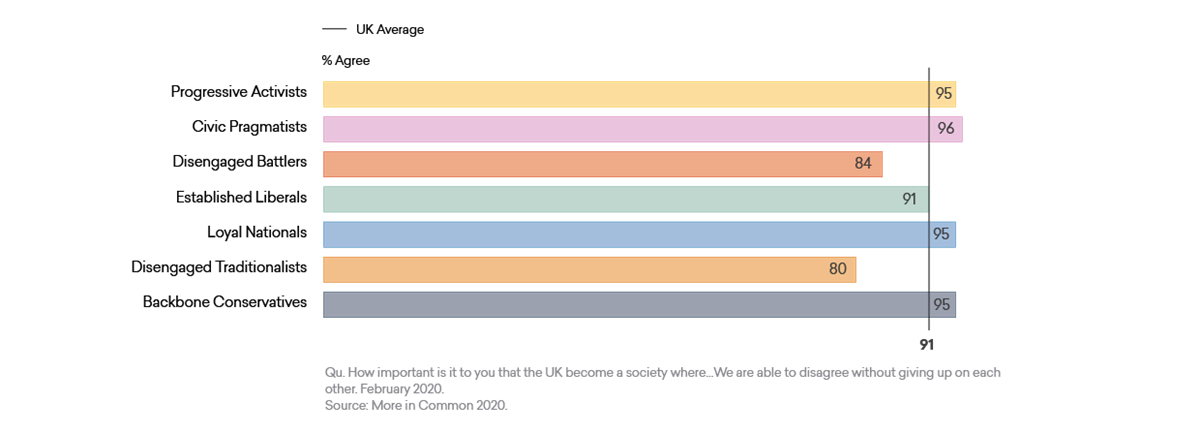

One path leads to the deepening polarisation that is being experienced in other countries, where ‘us-versus-them’ dynamics shape our national debates, causing distrust and even hate between people on either side of the divide. The other path leads to a more cohesive society that reflects one value shared by 9 out of 10 Britons - that we don’t give up on each other just because we disagree. That requires us to focus on building on our common ground, fixing the ‘burning injustices’ and realising our dreams of a harder working, more environmentally friendly and more compassionate Britain.

The Covid-19 pandemic has strengthened our belief that this is a moment for change. There is a rare opportunity to bring people in Britain together around new agendas for the 2020s in which we fix what we know is broken in our society, while also preserving those things that we treasure the most. Two in three of us say we need to make significant changes. In no major western democracy have we found a stronger appetite for change than in Britain.

We can all make this choice. We can choose the path we take into the 2020s. It starts with us understanding each other better, our values, our fears and our dreams. It can build from local communities, where two-thirds of us believe we can make a difference. Alongside leaders at every level of society and our local communities, we can step up and build a society that more truly reflects our common values and dreams.